The History of Rich Hill

by Dave Taylor

During the wee morning hours of April 16, 1865, two men and their guide approached the door of a darkened, Charles County, Maryland home named Rich Hill. “Not having a bell,” one of its sleeping occupants later recalled, the door was, “surmounted with a brass ‘knocker’.” One of the three horseback men, under the cover of darkness, reached out a hand and grasped the brass tool. He raised it upwards and, as the hinge reached the apex of its journey, the knocker was silently suspended for the briefest moment in time. In a fraction of a second, the handle would fall, striking the metal plate beneath it and “in the stillness of night the sound from this” would resound, “with great distinctiveness”[1]. The silence of the night would be shattered and the lives of the family sleeping within the house’s walls would be changed forever. History was knocking at the door of Rich Hill and its harbingers were John Wilkes Booth, the assassin of President Lincoln, and David Herold, his accomplice.

While Rich Hill would become known in American History due to the visitors that April night, the house and property had a notable history starting about 200 years before. In April of 1666, a recent immigrant from Wales named Hugh Thomas was assigned and patented “600 acres of land, called Rich Hills, on the west side of the Wicomico river, in Charles county, Md.”[2] Two years later, Hugh Thomas would sell half of his acreage at “Rich Hills” to an English immigrant turned St. Mary’s County merchant named Thomas Lomax. Lomax paid Thomas using the standard currency of the day: tobacco. For 3,500 lbs. of tobacco, Lomax acquired the northernmost 300 acres of the Rich Hill parcel, upon which the notable house would later be built.[3] In 1676, Thomas Lomax gave his brother Cleborne (also spelled Claiborne/Cleiborne) Lomax 100 acres of the Rich Hill property. When Thomas died in the early 1680’s, he was apparently unmarried and without any heirs and so the remainder of his Rich Hill property went to his brother as well. In 1710, the Rich Hill land was sold out of the Lomax family to an intriguing widow by the name of Mary Contee.[4]

A trifecta of circumstances had made Mary Contee nee Townley a very wealthy woman:

- Mary Contee’s late husband, John Contee, had previously married a wealthy widow by the name of Charity Courts in 1703. When Charity died the same year of their marriage, John Contee inherited her sizable estate. He and Mary were then married by June of 1704.

- In the same year of her marriage, Mary Contee’s cousin, Col. John Seymour was appointed the 10th Royal Governor of Maryland. Mary is recounted as a “favored cousin” of the Governor and due to this her husband John was appointed to several lucrative governmental positions becoming a representative of Charles County in Maryland’s Lower House and a justice in Charles County to name a couple.[5]

- Thus far, it has only been shown that John Contee had become a wealthy man. While Mary assumedly enjoyed the fruit of his abovementioned “labors”, how did she herself become wealthy? That is where the real drama comes in. John Contee died on August 3rd, 1708. At the time of his death he possessed 3,697 acres of land and his personal property was assessed at 2,252 pounds sterling and 13 slaves. According to his will which was passed by an Act of Assembly in 1708, Mary became the sole executrix of her husband’s vast estate. However, it was later discovered that this will was not as it seemed. In 1725, seventeen years after Mary Contee had inherited her husband’s holdings, John Contee’s blood nephew, a man by the name of Alexander Contee, had depositions taken with regards to the will that had made Mary such a wealthy woman. Through these depositions Alexander Contee learned that John Contee’s will was a perjured fraud that was never agreed to by the deceased. Alexander discovered that his uncle’s supposed will had actually been written by a man named Philip Lynes. According the Alexander, Mr. Lynes was a man “very officious to oblige the said Mary” while John Contee was dying in the next room. Philip Lynes was married to Anne Seymour, the Governor’s sister and therefore was also a cousin to Mary Contee. The will was apparently brought before John Contee who was still of sound mind, and he refused to sign it as it was written. Though Contee lived for about a week more, the will was never rewritten in terms he agreed to. Due to these depositions, the Maryland Assembly passed another act in 1725 repealing the 1708 act that had granted Mary Contee as sole executrix. The new act mentioned not only the maleficence of those who gained by this false will, but also the fraudulent way a knowingly unsigned will passed the Houses in the first place. According to the new act, the fake will passed due to, “particular persons in power by whose Interest and Influence the said Act past both Houses of Assembly… contrary to the Standing rules of The Lower House.” Perhaps Gov. Seymour, who was still in office in 1708, used his influence, once again, to intervene on behalf of his “favored cousin”.[6]

Therefore, it appears that Mary Contee purchased the Rich Hill property with fraudulently acquired capital. She did not own it for very long, however. By 1714, she had remarried a man by the name of Philemon Hemsley who facilitated the selling of the Rich Hill land for 21,000 lbs. of tobacco. The new buyer was Gustavus Brown.[7] Brown was a native of Dalkeith, Scotland and a surgeon by profession. His immigration to Maryland was an accidental one:

When a youth of 19 he became a Surgeon’s mate, or Surgeon, on one of the royal or King’s ships that came to the Colony in the Chesapeake Bay, 1708. While his ship lay at anchor he went on shore, but before he could return a severe storm arose, which made it necessary for the ship to weigh anchor and put out to sea. The young man was left with nothing but the clothes on his back. He quickly made himself known, and informed the planters of his willingness to serve them if he could be provided with instruments and medicines, leaving them to judge if he was worthy of their confidence.[8]

Brown started his medical practice in the Nanjemoy area of Charles County and quickly made a favorable reputation for himself. In 1710, he married a woman by the name of Francis Fowke and the newlyweds lived temporarily with her father in Nanjemoy.

Dr. Gustavus Brown, Sr. Source: Smithsonian Institutions

Dr. and Mrs. Brown’s 1714 purchase of the Rich Hill property ushered in a new age for the estate. Instead of solely using the land for the planting and harvesting of tobacco, Dr. Brown sought to create a home on the land. It is this home that we see today and know as Rich Hill.

The exact date of construction on Rich Hill has not been determined. According to its listing in the National Register of Historic Places, the house was “built probably in the in the early to mid 18th century”[9]. Looking at the genealogical records for Dr. Brown’s children, this author has determined that the house was built by 1720, as his daughter born that year was cited to have been born at “Rich Hills”.[10]

As it is today, Rich Hill was built as a 1 ½ story structure that appears as a full 2 story building from the exterior. The original house had a hip roof and was built on top of cut stone piers. While the front door was on the southwest side of the house as it is now, it was formerly on the center of this wall. As you walked into Dr. Brown’s Rich Hill, the first floor consisted of four similarly sized rooms with a small stair hall in back flanked by a rear door. The original building had two exterior chimneys which stood on the southeast and northwest sides of the house.[11]

The majority, if not all, of the Brown children were born at Rich Hill. Dr. Brown and Frances had a total of twelve children as his practice prospered. He had made a name for himself on both sides of the Potomac, treating residents of Maryland and Virginia. One humorous story regarding Dr. Brown’s experiences as a physician is recounted below:

On one occasion Dr. Brown was sent for in haste to pay a professional visit in the family of a Mr. H., a wealthy citizen of King George Co., Va., who was usually very slow in paying his physician for his valuable services, and who was also very ostentatious in displaying his wealth. In leaving the chamber of his patient it was necessary for Dr. B. to pass through the dining room, where Mr. H. was entertaining some guests at dinner. As Dr. B. entered the room a servant bearing a silver salver, on which stood two silver goblets filled with gold pieces, stepped up to him and said, ‘Dr. B., master wishes you to take out your fee.’ It was winter, and Dr. B. wore his overcoat. Taking one of the goblets he quietly emptied it into one pocket, and the second goblet into another, and saying to the servant, ‘Tell your master I highly appreciate his liberality,’ he mounted his horse and returned home.[12]

While his business grew, Gustavus Brown did suffer some of his own tragedies at home. Out of his twelve children with Frances, three died in infancy. In an odd twist, all of the children who died were boys who were named after their father. Dr. Brown himself was actually the second Gustavus Brown as his father in Scotland bore the same name. Dr. Brown named his first two boys, “Gustavus”, only to watch them both die before they were a year old. When his third son was born, Dr. Brown gave him the name Richard, and this son would survive. Perhaps thinking their curse of losing their male children was at an end, the couple named their fourth son “Gustavus Richard Brown” only to witness him perish 10 days after his birth. While not documented, it is extremely likely that the three infant Gustavus Browns were buried somewhere on the Rich Hill property.

Frances Fowke Brown Source: Smithsonian Institutions

Frances Fowke Brown died 1744 and was buried at the estate of her daughter and son-in-law in Stafford County, VA. Dr. Brown remarried a widow named Margaret Boyd in 1746. With Margaret, Dr. Brown had two more children at Rich Hill, a boy and a girl. Though tempting fate, Dr. Brown named his youngest son after himself. This “Gustavus Richard Brown” born on October 17th, 1747, would survive infancy, follow in his father’s footsteps into the medical profession, and enter the history books as one of George Washington’s friends and caregiver at the Father of Our Country’s final hour. Dr. Brown’s other child with Margaret was named after her mother and would later marry Thomas Stone, a signer of the Declaration of Independence from Maryland. Their shared home, Habre de Venture, in Port Tobacco, MD is a National Historic Site run by the National Park Service.[13]

In April of 1762, the senior Dr. Brown died at Rich Hill. His death was from “apoplexy” which was a general term that meant death happened suddenly after a loss of consciousness (i.e. severe heart attack or stroke).[14] Dr. Brown was buried at Rich Hill, though the exact spot of his grave is lost today.[15] Rich Hill and its 300 acres passed to his wife Margaret and then to his eldest son Rev. Richard Brown (who was also a medical doctor) and his wife Helen.

Rev. Richard Brown Source: Smithsonian Institutions

During his tenure in the house, Rev. Brown, through marriage and purchase, managed to acquire a large portion of the 600 acre Rich Hill parcel that was split back in 1668. A tax assessment for Rich Hill in 1783 shows Rev. Richard Brown owning 566 acres of Rich Hill. He also made some unknown “improvements” to the property, which probably entailed some work on the house.[16] When Rev. Brown died in 1789, Rich Hill and its acreage swapped hands a few times between his descendants, with a loss of some of the land the Reverend had managed regain.

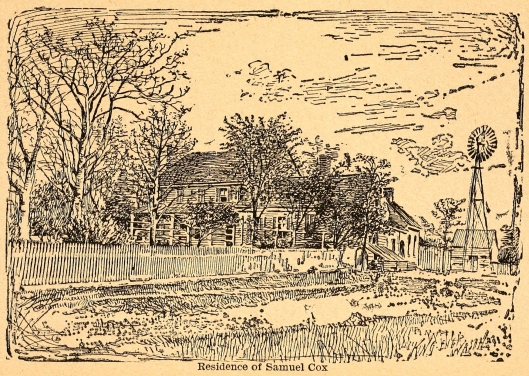

The Brown family owned Rich Hill continually for 93 years. At least four generations of Browns had made that house their home. It raised the men and women who befriended and married America’s founding fathers. When it was sold out of Brown family in 1807 to a man named Samuel Cox, a new chapter for Rich Hill began. The new owner and his descendants would own Rich Hill for the next 164 years and would witness the night history came knocking on their door.

Samuel Cox, the new owner of Rich Hill, is not the same man to whom John Wilkes Booth appeared to in 1865. Rather, this Samuel Cox was the latter’s maternal grandfather. From Samuel Cox, Rich Hill descended to his daughter Margaret who had married a man by the name of Hugh Cox. What relation, if any, existed between Margaret Cox and Hugh Cox has yet to be determined. Hugh and Margaret had five children born at Rich Hill, including their son Samuel, named for his grandfather. Samuel Cox was born on November 22, 1819. When Samuel’s mother, Margaret, died, his father Hugh found himself a new wife, Mary Ann T. T. Cox. Hugh had three more children by Mary Ann.[17]

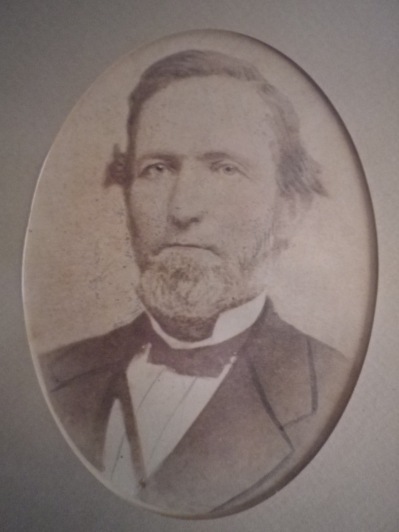

When Samuel Cox was 15 years of age, he was sent to the Charlotte Hall Military Academy. He returned home three years later and followed in his father’s footsteps as a member of the wealthy planter class. On December 6th, 1842, Samuel Cox married his Washington, D.C. cousin, Walter Ann Cox. Walter Ann was named for her father who died a couple months before she was born. By the late 1840’s Hugh Cox and his wife Mary Ann, were residing away from Rich Hill on another property they owned near La Plata called “Salem”[18]. In 1849, Hugh and Mary Ann officially gave Rich Hill to Samuel Cox as a gift. Hugh Cox would die in December of that same year at the age of 70.[19] Rich Hill was now in the hands of the man who would give aid to the assassin of the President.

Samuel Cox, Sr.

Sometime in the first half of the 1800’s a significant amount of remodeling was done to Rich Hill. Whether the work was commissioned by Hugh or Samuel Cox is unknown. Regardless, both the exterior and interior of the house were drastically changed from Dr. Brown’s initial layout. The hip roof was replaced with a gable roof. The two chimneys on either end of the house were replaced with a large, double chimney on the northwest side of the house. On the southeast side, where one of the chimneys had been, the Coxes built a one story frame addition. This new addition contained a dining room and a bedroom in which Samuel Cox and his wife slept. The front door was moved from the center of the southwest wall to its current location right near the intersection between the southwest and southeast walls. The interior layout of the house was changed, too. Originally containing four similarly sized rooms with a rear stair hall, the layout was an end hall plan with a large front room and two small rooms to the rear. Much of the layout of Rich Hill today still follows the renovations done by the Cox family in the early 1800’s.[20]

Samuel Cox was a successful farmer and participated in many political and social groups in the county. Through the exertions of Samuel and his father before him, the Rich Hill farm prospered to 845 acres, even larger than its initial 600 acres in 1666.[21] Despite his success in farming, Samuel Cox, like another previously discussed owner of Rich Hill, had difficulty producing a namesake. None of his children with Walter Ann survived infancy. Instead, Samuel Cox ended up adopting his late sister’s son, Samuel Robertson. Though this younger Samuel had spent much of his life on his uncle’s farm and property, he was officially adopted and had his named changed to Samuel Cox, Jr. three days after his 17th birthday in 1864.[22]

Samuel Cox, Jr. was present at Rich Hill when John Wilkes Booth and David E. Herold arrived in the morning hours of April 16th. Years later, he would write about the night he was awakened so early by the sound of that brass knocker on the door:

There was at the time in the house, Col Saml Cox, his wife, his wife’s mother Mrs Lucy B. Walker, Ella M. Magruder, now my wife, two servant girls, Mary and Martha and myself. Pa’s bedroom was on the first floor – and to the extreme eastern end of the house, and to approach the front door, which opens into the hall, Pa had to pass through the dining-room, where Mary and Martha slept. The stairway to the 2nd floor is approached through a door midway the hall and at the head of this stairway Mrs. Walker slept. My room is on the second floor and directly over the hall and two windows in this room are immediately over the front door looking out upon the yard and lawn in full view of the road which approached the house. When I was aroused by the knock I jumped out of bed and went down in the hall and as I approached the front door where I found Pa standing with the door partially open with Mary standing just behind him in the doorway of the dining room only some six feet away…[23]

Samuel Cox, his adopted son, and their servant Mary Swann would claim to investigators that Booth and Herold were never allowed entry into the house and were, instead turned away almost immediately. Cox, Jr. would hold onto this story to his dying day, telling assassination author Osborne Oldroyd in 1901 that his father found the fugitives attempting to sleep in a gully close to the house the next morning. It was only then, according to Cox, Jr., that his father instructed his farm overseer, Franklin Robey, to guide them into a nearby pine thicket while he sent Cox, Jr. to retrieve Thomas Jones, who would care for the men during their stay in the pine thicket.[24] Other sources, however, including Oswell Swann, the ignorant guide of the assassin and his accomplice, would state that Booth and Herold spent a few hours inside of Rich Hill before they departed. Some later second hand accounts also speak of Booth and Herold entering Rich Hill during that early morning for food and drink. Regardless of whether or not the men entered the house, the knocking on the door of Rich Hill by David Herold secured the home’s role in the history of the 12 day escape of the assassin of President Lincoln.

Samuel Cox, Mary Swann, and Samuel Cox, Jr. were all arrested in the aftermath of Booth’s visit to their house. They were informed on by Oswell Swann, who brought the troops to Rich Hill at about midnight on April 23rd. The three residents were transported at first to nearby Bryantown. After getting Mary Swann’s statement of events, Samuel Cox, Jr. and Mary were released, only to be rearrested a couple of days later.[25] Samuel Cox, the elder, was transported up to Washington and was imprisoned at the Old Capitol Prison. Though the authorities strongly suspected that Cox had aided the fugitives, with Mary Swann contradicting the account of Oswell Swann, there was nothing to prove their beliefs. While imprisoned at the Old Capitol Prison, Samuel Cox wrote a letter to his wife on May 21st. Addressed to “Mrs. W. A. Cox, Port Tobacco, MD”, Cox recounts, in part, the degree of his imprisonment, “…I know my dear wife it will give you as much pleasure to inform you as it was for me to receive, permission just as your letter was received, to walk in the yard for exercise, which I have been deprived of until to day, having been confined to my room now for nearly four weeks.”[26] Cox was eventually released from the Old Capitol Prison on June 3rd, and returned home to Rich Hill to his waiting family.

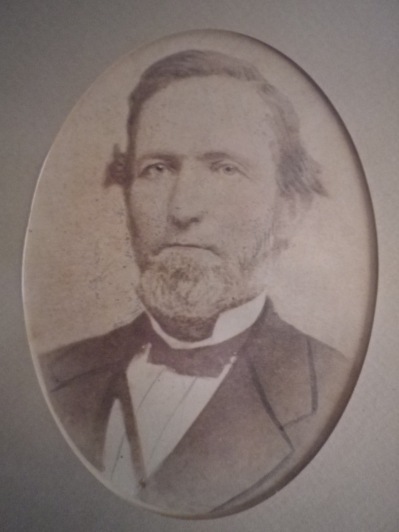

Samuel Cox, Jr.

The extent of Booth’s visit to Rich Hill remained quiet for a number of years. During the interim, Samuel Cox died on January 7th, 1880. In his will he left Rich Hill to his wife until her passing, after which the home and property would go to his only heir, Samuel Cox, Jr. In 1884, newspaper correspondent George Alfred Townsend (GATH) met with Thomas Jones. After years of silence, Jones shared with GATH his involvement in helping Booth and Herold during their “missing days” of the escape. Jones did nothing to shield the Coxes from their involvement, divulging how he was brought to Rich Hill by Cox, Jr. and how his father insisted Jones help get the men across the river when the time was right. In his article, entitled, How Wilkes Booth Crossed the Potomac, GATH describes Rich Hill:

The prosperous foster brother [Cox] lived in a large two-story house, with handsome piazzas front and rear, and a tall, windowless roof with double chimneys at both ends; and to the right of the house, which faced west , was a long one story extension, used by Cox for his bedroom. The house is on a slight elevation, and has both an outer and inner yard, to both of which are gates. With its trellis-work and vines, fruit and shade trees, green shutters and dark red roofs, Cox’s property, called Rich Hill, made an agreeable contrast to the somber short pines which, at no great distance, seemed to cover the plain almost as thickly as wheat straws in the grain field.[27]

Though Samuel Cox, Jr. was the man of the house, he officially became the sole owner of Rich Hill upon the death of his adoptive mother in 1894. By that time, Cox, Jr. had already married and had 3 children by his wife, Ella Magruder. These young Cox children, Lucy, Edith and Walter, grew up and were raised at Rich Hill. Ella died in 1890 and Cox subsequently remarried a cousin of his named Ann Robertson.

Like his father before him, Cox, Jr. became a prominent member of Charles County society. He had a sizable plantation with Rich Hill and he also owned Cox’s Station, a stop of the Baltimore and Philadelphia Railroad line that ran from Pope’s Creek on the Potomac up to Bowie in Prince George’s County where it connected to other lines. The modern town of Bel Alton (where Rich Hill is located) bore the name Cox’s Station up until Cox sold a sizable parcel of land to the Southern Maryland Development Company in 1891 and they renamed the area to its modern name. Cox, Jr. was also involved in local politics, running for and winning a seat in the Maryland general assembly in 1877. Dr. Mudd, another familiar name in the Lincoln assassination story, ran alongside Cox, but was not elected.[28]

Samuel Cox, Jr. died on May 5, 1906 at the age of 59. The ownership of the property passed to Cox’s son, Walter, who sold his share of it to his married sister, Lucy B. Neale. Lucy and her family did not live at Rich Hill. The last member of the Cox family to reside at Rich Hill was Samuel Cox, Jr.’s second wife, Ann Robertson Cox. Her death on March 4, 1930, marked the end of the Cox family’s habitation of Rich Hill.

Between the years of 1930 and 1969, Samuel Cox, Jr.’s grandchildren operated Rich Hill’s property as a tobacco farm for sharecroppers. The land shrunk back down to 320 acres by 1971. That year, Rich Hill and its 320 acres were sold to its current owner, Joseph Vallario, a senior member of the Maryland House of Delegates.[29] In celebration for the bicentennial of the United States in 1976, Delegate Vallario restored Rich Hill to its appearance during Dr. Brown’s day. This involved removing the front and back piazzas along with the one story addition that had been added by the Cox family in the 19th century.[30] Though this did make Rich Hill look less like the house that Booth and Herold saw on April 16, 1865, the restoration worked to preserve Rich Hill and keep it from falling down. Rich Hill served as a beautiful rental property for many years after.

As time passed, however, the house and property began to decay again. When no more renters were to be found, Rich Hill sat vacant and unattended. Mother Nature started eating away at Rich Hill. In 2014, a group of Charles County citizens approached Delegate Vallario about the possibility of him donating the property to either the Historical Society or the county government in order to save it from its slow descruction by the elements. Mr. Vallario agreed that the house deserved to be saved and preserved and graciously donated the house to the Charles County Government in 2014. The County, in cooperation with groups like Friends of Rich Hill, are working to preserve and restore this historic house for future generations.

While Rich Hill’s involvement in the story of Lincoln’s assassination is the house’s most discussed historical aspect, it is far more than the “stop on the trail of John Wilkes Booth” sign that stands some distance from it. As has been shown through this article, Rich Hill has had a notable and lengthy lifespan. It not only holds an important place in the history of Charles County, but it also affected the history of the nation due to the men and women who were raised under its roof. As a restored museum run by Charles County in conjunction with the Friends of Rich Hill and the Historical Society of Charles County, Rich Hill will continue to influence and affect the history of our nation.

Sources:

[1] Samuel Cox, Jr., Letter to Mrs. B. T. Johnson, July 20, 1891, James O. Hall Research Center.

[2] William F. Boogher, Gleanings of Virginia History: An Historical and Genealogical Collection (Washington, D.C.: W.. F. Boogher, 1903), 283.

[3] 26 Apr. 1668. Charles County Circuit Court Liber D, Page 14.

[4] 3 Mar. 1710. Charles County Land Records, Liber C#2, Page 245.

[5] Edward C. Papenfuse, A Biographical Dictionary of the Maryland Legislature 1635-1789 (Baltimore, MD: Johns Hopkins University Press, 1979), 230.

[6] Acts of the General Assembly hitherto unpublished 1694-1698, 1711-1729, Volume 38, ed. Bernard Steiner (Baltimore, MD: Lord Baltimore Press, 1918), 384-386.

[7] 12 Jan 1714. Charles Co. Land Records, Liber F#2, page 51

[8] Horace Edwin Hayden, Virginia Genealogies: A Genealogy of the Glassell Family of Scotland and Virginia : Also of the Families of Ball, Brown, Bryan, Conway, Daniel, Ewell, Holladay, Lewis, Littlepage, Moncure, Peyton, Robinson, Scott, Taylor, Wallace, and Others, of Virginia and Maryland (Wilkes-Barre, PA: E. B. Yorby, 1891), 152.

[9] National Registry of Historic Places Nomination Form, Rich Hill Farms (1976).

[10] Hayden, Virginia Genealogies, 162.

[11] Registry, Rich Hill Farms.

[12] Hayden, Virginia Genealogies, 153.

[13] Ibid, 147.

[14] Ibid, 151.

[15] Norma L. Hurley, “Samuel Cox of Charles County,” The Record – Publication of the Historical Society of Charles County, Inc., October 1991, 1-5.

[16] J. Richard Rivoire, Rich Hill Tract History (Charles County Historical Society).

[17] Hurley, “Samuel Cox”.

[18] “Mary Ann Cox Obituary,” Alexandria Gazette (Alexandria, VA), February 9, 1856.

[19] Hurley, “Samuel Cox”.

[20] Registry, Rich Hill Farms.

[21] Michael W. Kauffman, American Brutus: John Wilkes Booth and the Lincoln Conspiracies (New York: Random House, 2004), 250.

[22] David Taylor, “The Name Game,” BoothieBarn.com. August 24, 2013. http://boothiebarn.com/2013/08/24/the-name-game/

[23] Cox, Letter to Mrs. B. T. Johnson.

[24] Osborn H. Oldroyd, The Assassination of Abraham Lincoln (Washington, D.C.: O. H. Oldroyd, 1901), 267.

[25] Cox, Letter to Mrs. B. T. Johnson.

[26] Samuel Cox, Letter to Mrs. W. A. Cox, May 21, 1865, James O. Hall Research Center.

[27] George Alfred Townsend, “How Wilkes Booth Crossed the Potomac,” Century Magazine, April 1884, 827.

[28] Report of the Twelfth Annual Meeting of the Maryland State Bar Association held at Ocean City, Maryland July 3rd – 5th, 1907 (Baltimore, MD: Maryland State Bar Association, 1907), 75.

[29] Rivoire, Tract History.

[30] Registry, Rich Hill Farms